VI.The times of trouble

The period between the 1967 and 1977 elections, which we’ll cover on this page, witnessed the largest shake-up of the Dutch political system so far. The churches, especially the catholic one, released a large measure of control over their flocks, which led to the desegregation of Dutch society.

Secular PvdA and VVD reacted by taking extreme stands in order to draw left-wing and right-wing voters away from the crumbling christian parties. There was widespread confusion, with new parties popping up every election.

KVP and CHU lost voters at a prodigious rate, and the three christian parties decided to merge into the CDA, which first participated in the 1977 elections. In those same elections, PvdA and VVD decimated the small parties, and the three-party system was born.

Changes

If we oversimplify a bit we can say that these vast changes in Dutch politics were caused by the Vatican II Council. There the catholic church started on a vast project of renewal, one that a significant part of the Dutch catholic clergy supported.

The christian parties crumble

The christian parties tried to jump on the left-wing bandwagon, because they (wrongly) assumed it would keep their voters from moving to the left. Instead, they lost the left-wingers anyway and made their right-wing voters nervous.

Even CHU party leader Udink tried to keep in touch with the times. During the 1971 campaign he appeared on the Dam in Amsterdam and tried to connect with the hip, young people who’d taken it over. This incident was widely reported, and one wonders what the average CHU voter thought of Udink’s behaviour.

Contrary to reports Udink did not wear a long-haired wig during this visit. Still, the fact that he might have says enough about the sorry state of the christian parties during the times of trouble.

In 1954 the bishops threatened to excommunicate anyone who dared to become a member of a socialist organisation. It was the height of catholic unity. But thirteen years later a bishop remarked on TV that voting is a personal affair, and that catholics should follow their conscience.

Voting KVP was no longer required. Membership of a catholic trade union, newspaper, and broadcasting corporation was also not required. Liberated, ordinary catholics started to drift left and right. Formerly-catholic institutions started to find new ways of connecting to these voters, often also turning left or right. The catholic fortress crumbled.

The KVP was deserted, even attacked, by its inner circle of defenders: the clergy. Although only a minority of the clergy was active in the catholic renewal, it got a disproportionate amount of attention.

As to the voters, some of them felt liberated and moved away from the KVP to left- or right-wing secular parties. As a result the KVP started to haemorrhage seats. 8 lost in 1967, an additional 7 in 1971, and again 8 in 1972.

A similar process took place in the Hervormde Kerk, although it was less visible, less radical, and less influential. The christian-historians made a slide similar to the catholics, and lost 6 out of 13 seats.

As to the Gereformeerden, they were distinctly less touched by these developments. Although they, too, lost members, the Gereformeerde denomination, which has always been the core of the protestant camp, survives to the present day, and in the early seventies the ARP did not share the deep fall of KVP and CHU.

The secular parties polarise

Secular parties PvdA and VVD wasted no time in capturing these newly-liberated voters. Essentiallythey only had to open their mouths and bunches of seats dropped in of their own accord. The only thing the two secular parties needed was a clear profile, and that they speedily supplied.

In the late sixties the lay of the land was left-wing, so it’s no surprise that the left took the lead in attacking the christian parties. Basically, the left wanted a generic progressive/conservative division of Dutch politics, and wishy-washy, now-left-then-right christian parties did not belong in that system.

Besides, voters casting off the dogmas of the churches would see the left was their only logical choice — wouldn’t they?

In reaction to this left-wing polarisation, the VVD started up its own conversion programme, hoping to draw right-wing voters. There is an important difference with the left, though: where the PvdA aimed its attack at the christian parties, the VVD attacked the PvdA. Thus it not only spared the sensibilities of christian voters who didn’t want to entirely give up on their church, it also made the VVD a more alluring coalition partner for the decimated remains of the christian parties.

Results

PvdA and VVD got results. In ten years, the christian parties lost 26 seats, of which 14 went left and 12 right. This amounts to the following:

| Block |

1963 |

1972 |

Absolute |

Relative |

| Christian |

80 |

54 |

- 26 |

- 33 % |

| Left |

51 |

65 |

+ 14 |

+ 27 % |

| Right |

19 |

31 |

+ 12 |

+ 63 % |

The left made much of this, and true, its strategy of polarisation gave it a permanent boost in voters. Still, in the end the progressive Den Uyl government was only possible thanks to the support of some catholics and anti-revolutionaries. The left never conquered an absolute majority.

The left was far larger than the right to begin with, so one could say the right is the actual winner of the times of trouble. The left won about 25%, the right about 60%. That’s a clear difference.

The 1967 elections

Piet de Jong (1915-2016; KVP), defence minister 1963-1967, prime minister 1967-1971.

A navy officer when the war broke out in 1940, De Jong fled to England on a half-built submarine. During the war he served as first officer, later as captain, against the Germans, Italians, and Japanese.

After the war he became aide to the navy minister, later to the Queen, and still later secretary of state for the navy and defence minister. His quick career was helped by the fact that he was one of the very few catholic navy offciers when the KVP was allotted the navy secretariat. He was a specialist minister, rarely venturing outside defence territory.

In 1967 the KVP leadership unexpectedly moved De Jong to the top slot. He is credited personally for the stability of his government; nowadays he’s considered maybe the best post-war prime minister. He explains it by his submarine experience of making very different people work together.

In 1971 he was brusquely removed. It’s not entirely clear why, but before his prime-ministership De Jong had never belonged to the KVP’s uppermost ranks, and apparently someone with more clout in the party wanted the top spot (which, incidentally, went to the ARP).

He was occasionally active even at a very advanced age, denouncing the CDA cooperation with the PVV during the 2010 special party congress.

When delicately asked for his opinion on pornography, a hot topic in the sixties, he replied “To my knowledge, pornography is the only medicine against seasickness.“

The 1967 elections were the first sign that something was wrong. The broadcast crisis, the switch from centre-right to centre-left, and Schmelzer’s Night had made people wonder about traditional politics, and voters wanted something new — not just the same boring old parties with their power games.

Newcomer D66, who phrased these feelings most adequately, won an astounding 7 seats. (Compare this to the 9 seats that changed hands in total in the 1963 elections.) The right-wing protest BP won four seats, which shows not all voters were looking for reasonable alternatives.

The KVP lost 8 seats. Worse, the christian coalition of KVP, ARP, and CHU lost its absolute majority in parliament; permanently, as it turned out. Fortunately the PvdA lost 6 seats, so the KVP remained the largest party. Still, this was a stunning setback.

The De Jong government

Although these voter movements were quite shocking for Dutch politicians, a perfectly normal centre-right government was quickly formed. It remained stable for the full four years, and it was the only really stable government from 1963 until the ascent of the CDA+VVD new-style centre-right coalition in 1977.

De Jong handled the radicalisation of the country pretty well, all things considered. Hippies and other long-haired young people took over the cities, especially Amsterdam, which quickly grew to be a worldwide centre of the hip and the new. Though centre-right, the De Jong government was not unthinkingly conservative. The divorce law was updated, anti-homosexual laws were repealed, and universities were allowed a more democratic structure.

Thus De Jong managed to keep a centre-right government abreast of the leftist spirit of the age.

KVP and PvdA under stress

The 1967 elections had been a nasty surprise for both KVP and PvdA. Both concluded that something had to change, and both lost parts of their extreme wings.

It was clear to the christian parties that their absolute power was slipping. Quite apart from the problem of a vanishing majority, this also meant that the KVP was overtaken by the PvdA as largest party in the country, and Dutch custom allows the largest party to take the initiative during government formation. Prominent members of all three parties started to think about a merger, from which eventually, ten years later, the CDA would spring.

Within the PvdA, a collection of mostly young politicians challenged the old guard, who was charged with out-of-touch policies that caused the gradual erosion of the social-democratic vote. This movement was successful and drew the party leftward, even though it never outright controlled the PvdA.

In addition, both KVP and PvdA lost three seats during the parliamentary period by split-offs. In the case of the KVP left-wing politicians broke away and founded the PPR, reinforced by some anti-revolutionaries. The PvdA saw the opposite: a concerned group opposed the changes Nieuw Links proposed and split off to form DS70.

Polarisation on the left

Left-wing politics were hip and happening in the late sixties and early seventies. As largest left-wing party, the PvdA was supposed to profit from this, but that materialised fairly slowly. Instead of flocking to one huge party (as the social-democrats no doubt hoped), the left was denominationally segregated, with separate parties for socialists, christians, and liberals.

Nieuw Links

Within the PvdA, the Nieuw Links (New Left) group started propagating a far more left-wing course than the cautious party bosses found desirable. Nieuw Links, founded in 1965 but only getting an impetus after the disastrous 1967 elections, argued that the PvdA did so badly because it was too centrist for new, young voters, as well as part of the traditional electorate.

From then on Nieuw Links gathered force, won a string of intra-party elections, and became more powerful and outspoken. In 1970 they won a majority in the party leadership committee, and from then on they tried to influence the parliamentary fraction, and later on the Den Uyl government.

Party leader Den Uyl, freshly appointed in 1967 and not a Nieuw Links man, allowed the group to take over part of the party system in exchange for their support for his leadership. He also tried to bridge the gap between newcomers and old guard — not always successfully.

Progressive Agreement

In addition to reinvigorating the party programme with new-left ideas, the group aimed for a complete restructuring of Dutch politics along Anglo-Saxon lines. It envisioned two large, broad popular parties, one progressive and one conservative, vying for power in the state. Obviously, the PvdA should form the core of the progressive one.

As a first step towards such a progressive popular party, PvdA, D66, and PPR came to a closer cooperation in the so-called Progressive Agreement. The parties agreed to cooperate as much as possible on all levels of government. The three parties created common lists for several local elections, and combined their lists for the national 1971 and 1972 elections.

Initially the PSP was also invited to enter the Agreement, but the pacifist-socialists preferred to keep their purity intact. The communists of the CPN were deemed too left-wing and Moscow-loyal even by the other parties of the left, and they were not invited.

Cooperation was not perfect, however. D66 and PPR were a bit afraid of the influence of the overwhelmingly larger PvdA.

In 1971 the Progressive Agreement formed a UK-inspired shadow government. Thus they clearly showed what the alternative to the centre-right coalition would be, while simultaneously placing the border between Left and Right straight between the Progressive Agreement and the christian parties. They also indicated their coalition preferences: any PvdA, D66, or PPR voter would know in advance with whom their party was going to cooperate.

KVP forced rightward

All this was aimed againt the KVP. It was hoped that the clear dichotomy Progressive Agreement vs. Christian Parties would be translated into Left vs. Right. Thus the conservative wing of Dutch politics would be thought of as KVP-headed, which, it was hoped in circles on the left, would give left-wing catholics a reason to jump to the PvdA. This entire set of conclusions was validated because the KVP cooperated in once centre-right coalition after another, and some voters did make the move to the left.

So the point of the deliberate polarisation strategy by Nieuw Links became forcing the KVP into the right wing. Besides, Schmelzer’s Night had destroyed any confidence PvdA leaders may have had in the KVP, and therefore it wasn’t hard to get social-democratic leaders to agree on an outright ban of the KVP.

Thus the PvdA declared that, no matter what, it would not form a coalition with the KVP. Thus the KVP was firmly placed on the right, and the left had clearly stated its coalition preferences.

A new era in politics was about to start. Wasn’t it?

Well, not according to a few disgruntled old-guard PvdA members, who felt their party was moving too far to the left. As a result they founded DS70, which was admitted to the next government coalition, and which we’ll treat in more detail below.

The 1971 elections

In 1971 the Progressive Agreement was campaigning against the christian parties in particular, but its goal was of course defeating the entire centre-right coalition. That plan succeeded. All coalition parties lost seats, and their total went down by 12 seats to 74, a minority. Better still, the majority of this loss went to the Progressive Agreement: the three parties had 8 new seats to divide among each other. Still, that only brought them to 52 seats.

The big winners were DS70, which entered parliament with one seat more than D66 in the previous elections, and D66, which went from 7 to 11. The PvdA gained 2 seats, proving that the electoral tide had reached its lowest point in 1967 and was now slowly moving back to flood.

The Biesheuvel governments

The PvdA had become the largest party and could take the initiative, but as it had promised it refused to work with the KVP, and since centre-right maintained its unity, that was the end of any possible leftish government.

Thus the centre-right parties headed by the KVP had to solve the electoral puzzle. Fortunately one solution was rather obvious: why not invite big winner DS70, which seemed to consist of social-democrats who could be relied on to cooperate with the right? The new party quickly agreed.

Thus the Biesheuvel government was formed. Due to the delicate political situation the catholics preferred an ARP prime minister to take the blame if anything went wrong. And wrong it went.

The DS60 ministers weren’t too professional, and the party was torn between traditional left-wing issues such as affordable education, more right-wing issues such as fiscal responsibility, and an understandable desire to create its own profile in the hodgepodge of fourteen parties that was parliament, and the five parties that sat in government.

Within a year government fell over a DS70 refusal to accept a fiscal plan supported by the other government parties. A caretaker government of the other four was formed and new elections were called.

Creation of the CDA

Piet Steenkamp (1925-2016), first CDA chairman 1973-1980; KVP and CDA senator 1965-1999.

Piet Steenkamp was one of the driving forces behind the creation of the CDA. He was involved in the merger from the very beginning with the Group of 18 in 1967, and gradually became the face of the new merger party.

In 1973 he became chairman of the “Federation CDA,” a rather vague cooperation of KVP, ARP, and CHU that slowly grew into a merger party. Although the CDA entered the 1977 elections with one common list, officially the party wasn’t founded until 1980, when KVP, ARP, and CHU were disbanded. At that point in time Steenkamp resigned as chairman because his job was done.

He was very popular with the common members and voters; not only catholics, but also protestants. This gave him the strength to survive the endless meetings and petty squabbles between catholics and anti-revolutionaries, who might believe in the same Gospel but had quite different cultures.

Soon after the diastrous 1967 elections it became clear to KVP, ARP, and CHU, that they had to take decisive action in order to stay in the centre of Dutch politics. Merger talks were started, and although all three parties quickly agreed that this was something to be looked into seriously, decisive action in christian-democratic circles means talking for ten years. And that’s what they did.

There were large cultural differences between catholics and anti-revolutionaries, which were increased because the ARP made a lurch to the left under party leader Aantjes. With the CHU still favouring the right and the KVP in the centre, this did not help the merger programme.

In 1972 the three parties presented themselves as a block, just like the Progressive Agreement did, as we’ll see below. The losses continued, and during government formation several left-leaning KVP and ARP leaders allowed themselves to be brought into the Den Uyl government. KVP and ARP more-or-less supported that government, while the CHU was in the opposition. That did not help form a cohesive merger party.

Still, talks continued, and committe after committee reviewed and re-reviewed the proposed tenets of the new party, which had to spare both catholic and protestant sensibilities. Nonetheless the new party’s name was found: CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal.

At the first common CDA conference in 1975 the fateful decision was taken to enter the next elections with a common list. Although this was a major step forward, the proceedings were marred by ARP leader Aantjes’s “Sermon on the Mountain,” in which he declared he wanted to follow a left-leaning policy aimed at helping the poor — as the Gospel requires. KVP and CHU were not amused, and the formation of the CDA was once more delayed.

The 1977 elections were a success in the sense that the disastrous seat loss was stemmed and the christian parties returned to the centre of power with the formation of a CDA+VVD centre-right government. Still, it took the old parties until 1980 to officially disband themselves and fully merge into the new CDA structures.

Thus ended the Anti-Revolutionary Party that modeled so much of the Dutch political system and its history. Thus also ended the catholic party and its southern one-party state, that had dissolved in the previous elections.

The difference between the anti-revolutionary and catholic “blood types” is still readily apparent even today. An unofficial rule came into being where the CDA party leadership would switch between catholics and protestants, with catholic justice minister Van Agt selected as the first leader. Catholics and anti-revolutionaries succeeded one another as party leaders. Christian-historians were generally less visible, and it wasn’t until 2012 that the CDA got its first party leader from the CHU blood type.

Survival of the protestant denomination

With the dissolution of the KVP the catholic denomination ceased to exist. On the protestant side of the fence, however, things went differently. ARP and CHU were not the only protestant parties, after all. SGP and GPV still had their own following, and they weren’t about to forget their historical opposition to, respectively, the catholics and the anti-revolutionaries.

Besides, the small protestant camp was reinforced by the RPF, which consisted of ARP and CHU members who couldn’t stomach being in the same party as catholics. Cooperation is all very well, but a protestant should be able to vote for a protestant party.

Thus a sliver of the protestant denomination continues to exist to the present day, and it even entered government in 2006.

1972 and Den Uyl

Joop den Uyl (1919-1987), economics minister 1965-1966, PvdA party leader 1967-1986, prime minister 1973-1977, minister of social affairs 1981-1982.

Born in a Gereformeerde family, he tended leftward quite early in his life. During the war he helped publish the illegal social-democrat newspaper Het Parool, and after the liberation Den Uyl was a journalist on the left side of the spectrum for a while.

He became alderman of Amsterdam in 1963 but gave up that post to become economics minister in the Cals government that fell in Schmelzer’s Night. After the PvdA’s loss in 1967 he became party leader, which he was to stay for twenty years.

Although not part of Nieuw Links himself, he supported their ideas and it was on their platform that he led the Progressive Agreement and became prime minister.

Den Uyl was a charismatic leader who did well with large swaths of the Dutch population, including the first wave of immigrants. Nonetheless he wasn’t much of a manager, as the history of his government shows.

After being defeated in the 1977 formation he remained the great polariser on the left, which led to the fall of the Van Agt II government in 1982. Den Uyl resigned after the 1986 elections, and died only a few months after, authentically mourned by both left and right.

The 1972 elections by and large confirmed the 1971 ones. The Progressive Agreement still acted as one power block, and the christian parties copied that behaviour pending the merger.

The battle between the two blocks ended in a clear left victory. The christian parties lost yet another nine seats, which were equally divided between left and right. Even more ominously, the KVP lost its absolute majority in the south, and both PvdA and VVD profited and won scores that are comparable to their national ones.

Nonetheless the Progressive Agreement did not even come close to a majority. PPR and PvdA won, but D66 lost heavily, and the block gained only four seats net. On the right, the VVD started to suck seats from the other right-wing parties, though not yet enough to help the christian parties to a majority.

The old coalition, including DS70, still maintained a razor-thin 76 seat majority, but the centre-right parties didn’t feel like a repeat performance, and there were no other candidates for the role of fifth party in government. Besides, the country clearly felt that the right wing

had had its chance and blown it. Now the left was allowed to try.

Den Uyl

PvdA leader Den Uyl was in exact the same position as Drees had been in 1956. The left had won a clear-cut victory but no majority. In order to create a workable government it would have to cooperate with the christian parties in the centre, especially the reviled KVP. But the PvdA had sworn not to work with the KVP.

The solution was to cooperate not with the KVP as a party, but with individual left-wing politicians within the KVP on a more-or-less personal title. This approach was extended to the ARP. There were precious few left-wingers within the CHU, so that party was dropped. It wasn’t necessary for a majority, anyway.

The formation dragged on for months, mostly because Den Uyl insisted on a progressive majority within government, and because individual KVP and ARP politicians had to be carefully massaged. In the end Den Uyl formed a minority government, because only PvdA, PPR, and D66 officially committed to the government programme. KVP and ARP did not, and one of the unenviable task of the christian ministers was to gather together enough christian votes for a majority every time government wanted something done.

The Den Uyl government was something of an all-star cabinet, with future prime ministers Van Agt and Lubbers (both KVP, soon-to-be CDA) as well as future Dutch, and later European, Bank director Duisenberg. Unfortunately all these stars had personalities to match, and fights were the order of the day.

The tension between Den Uyl and Van Agt, especially loomed large, and they occasionally fought a little private war in the press, wholly outside the normal governmental and parliamentary arena. This tension was largely personal, but there were some political components. Van Agt tried to profile himself as a conservative especially with regard to abortion. Without informing Den Uyl he tried to close the first Dutch abortion centre, which led to a frightful row.

structural problems were added to these personal ones. The depression of the seventies set in, and the oil crisis deprived the Netherlands of necessary oil imports for a while, causing government to institute the car-less Sundays in order to save energy. Still, the depression was the most serious problem, especially for a government elected on a platform of keeping the welfare state going and maybe even extending it a bit.

A few months before the end of its natural life government fell over the umpteenth fight between Den Uyl and Van Agt. New elections were called.

It is important to recognise that the Den Uyl government was a temporary break in a series of centre-right governments stretching from 1959 to 1986. Although Den Uyl tried to break this tradition, and would try again in 1981, he essentially failed to do so. Probably the polarising attitude of the PvdA did not help here.

The right

Hans Wiegel (1941), VVD party leader 1971-1982, interior minister 1977-1981, Queen’s Commissioner in Friesland 1982-1994.

In 1982 he left national politics to become Queen’s Commisioner in northern Friesland. Still he kept the national VVD on its toes by his proclamations from his northern fortress, usually amounting to “I’d have done this totally differently.”

Although his heydays are long gone, he is popular with right-wing VVD voters to the present day. Every five to seven years he does something wild that briefly shakes up Dutch politics, giving the right a pleasant warm feeling and causing a knot in the left’s stomach.

In 1999 he received the ultimate political accolade: his very own Night. He was a senator then, and, breaking with the rest of the VVD, his vote was the decisive one that sent the D66 proposal for a corrective referendum to defeat. Prime minister Kok offered the resignation of his second Purple government, but the Queen refused, and the problems were patched up. Nonetheless, after Wiegel’s Night the Purple fairy tale was over.

Debate between Den Uyl and Wiegel.

During all these troubles the right was less unified than the left. That is understandable: where the small left-wing parties always have an ideology that clearly sets them apart from the PvdA and gives them political goals, the small right-wing parties have neither and are mostly protest movements. This meant that, even had it wished, the VVD could not lead the right-wing answer to the Progressive Agreement: the smaller parties would never agree on anything, and even if they had they’d fall apart in short order.

For the VVD, the story of the times of trouble was strikingly similar to the PvdA’s in some respects; totally different in other. The VVD changed a lot in these days. It started out as an upper-middle-class party, but during the times of trouble it acquired a populist tone of voice. Besides, with the left all polarising and spending like mad, it was quite easy for the VVD to profile itself as a fiscally responsible party that would do away with the leftist pipe dreams.

Party leader Wiegel fit this new VVD profile. He was the perfect man to guide the VVD’s transformation to a broad-based right-wing popular party. He

presented the VVD as the party of common sense, and transformed it the obvious party for defectors from the christian centre who didn’t want the socialists in power, and he built a following in especially the southern provinces with great rapidity.

Its tactics didn’t differ that much from the PvdA, except that it started a bit later and attacked mainly the PvdA; and not the christian parties it needed for a coalition. Quite apart from short-term electoral benefits, it never made itself an impossible partner for the CDA. On the contrary; as time progressed CDA and VVD started to feel like natural allies; something the VVD was to profit from in later years.

As a result the VVD grew from a mid-size to a large party, even though it has mostly remained the smallest of the large parties. The 1972 result of 22 seats was unprecedented in VVD history up until then, but compared to later years, 22 is a decidedly bad result.

In short, the VVD, too, profited from desegregation and polarisation, just as the PvdA did. In the 1977 elections Wiegel was vindicated because the VVD sucked the minor right-wing parties dry and went up to 28 seats.

Role of the small parties

As we saw at the start of this article, the net result of the times of trouble was the redistribution of about 25 seats from the christian parties to the PvdA and VVD. If that’s all that happened in the long run, why all the fuss with the smaller parties?

Why were the radicals, right-wing socialists, populist protesters, and all the rest necessary? Couldn’t the voters just have voted for another large party instead of messing around with new, small parties, wildly fluctuating election results, and general political chaos?

Apparently, no. Apparently, supporting lots of small parties for a short while is the process by which Dutch voters realign themselves. Apparently, lots of voters needed a stepping stone on the way from the christian centre to the left or right.

In retrospect it’s clear that the PPR conducted left-wing KVP and ARP voters to the PvdA, A KVP voter would not switch straight away to the PvdA; especially not when she’d learned to see this party as the enemy and “different”. Voting for that nice little party that was quite close to the PvdA but run by “our people” was quite acceptable, though. And after that first, crucial vote, migrating further to the PvdA had become only a small step.

D66 filled a similar role on the left, although it was clear that there was also a genuine left-liberal electorate that welcomed the VDB-reincarnated as a worthwhile addition to the Dutch political landscape.

On the right, DS70 and the BP did the same for the VVD. The right-wing social-democrats made it possible for traditional socialist voters that rejected the New Left to switch to the right wing, while the BP fulfilled a similar role for right-wing christian voters, especially those in rural areas.

Thus, the small parties had the function of a midway station; acceptable as a first step to a catholic KVP voter on her way to the PvdA, or a Hervormde CHU voter trending to the VVD.

D66 — the early years

Jan Terlouw (1931), D66 party leader 1973-1982, economics minister 1981-1982, Queen’s Commissioner in Gelderland 1991-1998.

Originally a physicist, Terlouw gained national fame as an author of children’s books. My generation grew up on them, and nowadays children still read them. Terlouw is thus one of the few politicians known primarily for his non-political work.

Entering parliament in 1971 he became party leader two years later, and it turned out that his soft-spoken centrist demeanour was exactly what D66 voters were looking for. Under his leadership D66 grew to its first major success in 1981 and Terlouw entered government. However, he was unable to keep Den Uyl and Van Agt from each other’s throats, and in the ensuing 1982 elections D66 was severly punished.

After stepping down Terlouw remained politically active in the fringes and he also continued his writing career. In the 2017 campaign he suddenly became visible again and gave a few well-regarded interviews on the importance of being reasonable and centrist. Since D66 leader Pechtold is a proponent of the centrist course that Terlouw pioneered back in the seventies (as opposed to party founder Van Mierlo’s more left-wing course), his help was gratefully accepted by the D66 party leadership.

In 1966, a diverse group of “politically homeless,” became irritated with the way the large parties, left and right, divided political power among themselves without the people as a whole having much say in the matter. They published the Appeal that we studied in the previous article and found that there was interest in founding another party, which became D66 (Democraten ’66; Democrats ’66).

Even better, in the 1967 elections they won seven seats; and that was extraordinary in the days of the ancien regime. For comparison: the total amount of seats that changed hands in the 1963 elections was nine. This was an entry on a grand scale; and it laid to rest the party founders’ fears that D66 would become one more in the interminable array of minor Dutch parties.

Party founder and leader Van Mierlo planned to cooperate closely with the PvdA, and he wasn’t averse to a full merger into a progressive popular party somewhat further down the line. However, the right wing of the party saw more in a continued independent existence, bridging the gap between PvdA and the christian parties.

After the initial success in 1967 and 1971 it turned out that the voters saw too little difference between D66 and PvdA. D66 began to slide down, and it was the only left-wing party to lose seats in the 1972 elections.

As a result Van Mierlo stepped down in 1973. Centrist Terlouw was elected as his successor, but he doubted whether the party remained viable. A motion to disband the party was supported by the majority of the membership congress, but not by the required two-thirds majority. Terlouw demanded 60,000 autographs before he accepted the top spot, and got them.

Under Terlouw’s leadership the party found its place as the reasonable alternative to the polarised PvdA and CDA for disaffected centrist voters. D66 recovered in 1977, and in 1981 it won 17 seats, far more than in any previous election.

Now D66 was strong enough to refuse to reinforce the CDA+VVD coalition and instead opt for a coalition with PvdA and CDA. Unfortunately PvdA’s Den Uyl and CDA’s Van Agt hated each other enough to implode the government, and Terlouw was unable to stop them and D66 suffered for it.

Terlouw quit, but a good successor was very hard to find. In the end D66 begged Van Mierlo to return, which he did in 1986. With the founder back in charge, D66 started to go up in the polls once more. Van Mierlo refused to enter the 1989 centre-left government, and this was a wise decision. D66 attained its second high in 1994, when it had the chance of a lifetime to change the Dutch political system. We’ll get back to this in due course.

DS70

Willem Drees jr. (1922-1998), son of the legendary PvdA prime minister, DS70 party leader 1970-1975, minister of Traffic and Waterstate 1971-1972.

A high functionary at the Finance department and mostly chosen for his family name, Drees turned out to be more of a civil servant than a minister. He irritated his colleagues by his unprofessional behaviour, and eventually resigned in the expectation that prime minister Biesheuvel would call him back. Biesheuvel didn’t, and that was basically that for DS70.

In reaction to the Nieuw Links movement, the PvdA’s right wing revolted. It wanted to stay the tried and trusted course of moderate social-democracy and cooperation with the Christian parties. Former prime minister Drees resigned from the party; he thought the Nieuw Links movement was impractical and unrealistic.

A new party, DS70 (Democratisch Socialisten 1970; Democratic Socialists 1970; the “1970” bit was a blatant rip-off from D66), was founded, and Drees’s son Willem Drees jr. was elected as its political leader.

The new party consisted of traditional social-democrats who weren’t interested in the young dogs’ leftist dreams. It refused cooperation with the radical left and supported cooperation with the NATO, something that was anathema to the left in those days.

Initially this party met with success, and it hoped to supplant the PvdA in the long term. However, its total failure in the Biesheuvel government put an end to that dream.

In later years DS70 shrank pretty quickly, especially after a split in 1975. In its last years the party entered decidedly authoritarian right-wing territory, and it was very hard to see what this party still had to do with social-democracy. It disappeared silently in 1981.

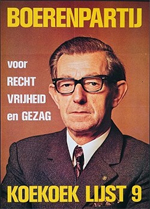

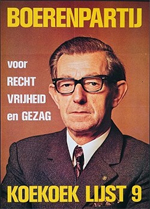

BP

Hendrik Koekoek (1912-1987), BP party leader 1958-1981. He was universally known as Boer Koekoek, and since koekoek means cuckoo, this can be translated as “Farmer Cuckoo.”

A popular singer once invited Boer Koekoek to participate in a topical and irreverent adaptation of a traditional song about an owl and a cuckoo aimed against prime minister Den Uyl (“the Owl”). This ornithological excursus made Boer Koekoek the first (and to date the only) Dutch politician to score a number 1 hit.

Koekoek’s dry humour and his penchant for translating deathless political prose to normal language had an appeal of their own, and his personality can be credited for a lot of the BP’s popularity.

The sixties aren’t complete without Boer Koekoek and his BP. Founded in 1958 by Boer Koekoek, a former CHU member, the BP (Boerenpartij; Farmers’ party) started out as one of the many populist parties angling for the right-wing protest vote. Predictably, it agitated against big government — in this case choosing the side of small farmers against the newly-minted Agricultural Council — and in the 1959 elections it was kind of lost in the crowd.

Just before the 1963 elections, though, government agricultural officials and police tried to evict a few farmers for non-payment of dues right in Boer Koekoek’s native village. The victims were assisted by about 200 farmers, and a battle with police ensued. Boer Koekoek appointed himself spokesman for the farmers, became nationally known and entered parliament with two other BP members. Interestingly, the BP was the first party to gain a decent score in the south, where non-catholic parties had always been at a disadvantage.

The times favoured protest parties. Koekoek took the step of connecting with the city-based conservative right-wing that was fragmented into dozens of microscopic parties. These voters helped him win his 1967 victory, when the BP increased from three to seven seats.

However, both before and after the 1967 election intra-party arguments — inevitably dubbed “Boer Wars” — led to the split-off of dissidents; and the second dissident group took four of Koekoek’s hard-earnd seven seats. The main problem was that Boer Koekoek wasn’t a very good manager, and that crucial things like party administration, or even its electoral platform, were hazily defined.

A worse problem was that one of these arguments was caused by a BP member having been a member of a minor national-socialist party back before the war. This caused the BP to be associated with the brown right wing of politics. Boer Koekoek’s counter-strategy of accusing random government parties MPs of Nazi sympathies didn’t help, even though he personally remained above all brown suspicions.

In the end, the party’s downfall, like its upswing, was not caused by its qualities, but by the start and end of the times of trouble, the fall and restoration of the old political order.

Note the three classic elements of Dutch populist parties:

- A charismatic front-man who’s not a real leader.

- A split within weeks of the elections, complete with dissidents and the creation of new parties.

- Dark mutterings about nazism, mostly caused by incompetent or non-existent vetting of candidates.

Now that I write this down it reminds me of largish right-wing parties in largish superpowers.

Continue

With the times of trouble at an end Dutch politics returned to a more stable period in the three-party system.